A modern high-speed grid aims to transform national logistics, cut travel time, and power India’s next phase of economic expansion.

Two decades after Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s Golden Quadrilateral redrew India’s highway map, the country is preparing for a sequel on an unprecedented scale a ₹20-trillion mission to build over 20,000 km of access-controlled expressways by 2030. This vast network will link metros, ports, and industrial hubs into a seamless, high-speed transport grid the largest outside China. The plan seeks to reduce logistics costs, spur industrialisation, and integrate the economy through faster, safer connectivity.

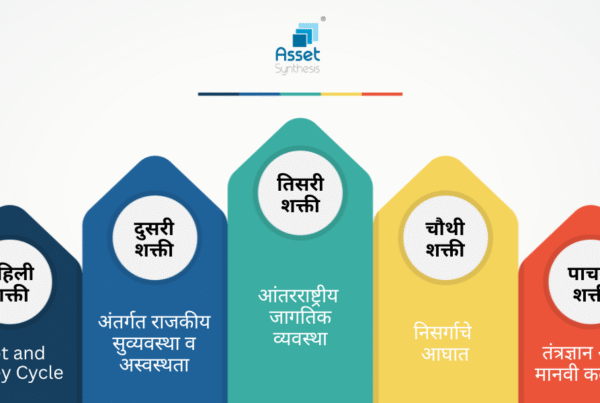

The New Blueprint: At the heart of the plan lies a “Golden Quadrilateral of Expressways” connecting Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, and Kolkata, complemented by two national spines the East–West Corridor (Silchar–Porbandar) and the North–South Corridor (Srinagar–Kanyakumari). Unlike the early 2000s network, the new corridors are fully access-controlled, six- to eight-lane, and engineered for 120 km/h speeds. With electronic tolling, grade-separated interchanges, and fenced perimeters, they mark a shift from open highways to true expressways.

Funding the Drive: The government estimates a total investment of ₹20 trillion over the next 5–7 years. Funding will flow from the National Infrastructure Pipeline, private PPP/BOT/TOT models, multilateral agencies such as JICA and ADB, and NHAI’s Invites and bond issuances. Asset monetisation remains central revenue from operational highways will be recycled into greenfield expressway development.

Transforming Connectivity: The expressway grid will dramatically cut travel time by 30–40% on key routes and lower logistics costs from the current 13–14% of GDP to below 9%. Such gains could boost manufacturing competitiveness and export efficiency. Industrial growth is already clustering along major routes such as the Delhi–Mumbai Expressway, which is nearing completion, and the Chennai–Bengaluru Expressway, expected to open soon. These projects are designed to integrate with logistics parks and digital traffic systems to optimise freight flows.

Progress and Hurdles: Over 2,500 km of expressways are operational, with tenders for another 19,000 km at various stages of execution. The target: a 20,000-km expressway grid by 2030. However, land acquisition, environmental clearances, and NHAI’s mounting debt remain challenges. The Centre is pushing digital acquisition systems and hybrid funding models to speed up execution and reduce delays.

The Economic Multiplier: Infrastructure economists estimate that every ₹1 invested in highways adds ₹2.5–₹3 to GDP through productivity and logistics gains. As Deloitte’s Bhavik Damodar notes, “A modern quadrilateral of expressways, backed by east west and north south corridors, can transform regional economies, generate employment, and anchor India’s next growth cycle.” In essence, India’s expressway revolution is not just about faster roads it’s about faster growth, greater integration, and a reimagined economic geography for the decade ahead.